MapReduce from Scratch

Building a distributed computing framework, step by step.

Over the last couple of weeks, I’ve been building MapReduce from scratch.

This will be a long article: we’ll understand the need for distributed computing, rediscover why MapReduce is a natural way to model many problems, build our own version, understand how individual parts fit together, and solve a real problem with it!

Motivating the problem

Suppose we want to count the word frequencies in a massive dataset. We tried to process it on a single machine but found it would take over a month. What can we do?

The first thought should be to get a faster machine, but it either might not exist or be too expensive. Instead, let’s see how we can distribute the problem across N commodity machines. We want an easy way to look up the frequency of any word with a simple query, i.e. grep over a file.

Let’s start by splitting the dataset into N partitions and computing word frequencies for each subset using a different machine. This already gives us Nx speedup minus some fixed overhead. To combine the results, we can add a final machine that takes these N partial result files and sums the frequencies of corresponding words.

This is not too far from the core idea behind MapReduce. The above process has two main steps: first, we map words to their frequency in a subset of input data and then reduce the intermediate results to obtain the final answer.

Note that this is pretty general, imagine we have a large dataset of photos that we want to classify: we could do the image classification task as a map operation and then group images with the same class in the reduce phase.

Another observation is that the map part is usually the more expensive phase of the two, so generally, we will have more mappers than reducers.

Having hopefully convinced you that MapReduce is a reasonable idea, let’s see how the MapReduce paper solves the word frequency problem.

Using MapReduce

Below, I copy-pasted the WordCounter MapReduce program from the paper. Let’s see how it works. Later, when we implement our version, we’ll aim to keep the usage semantics the same.

#include "mapreduce/mapreduce.h"

// User’s map function

class WordCounter : public Mapper

{

public:

virtual void Map(const MapInput &input)

{

const string &text = input.value();

const int n = text.size();

for (int i = 0; i < n;)

{

// Skip past leading whitespace

while ((i < n) && isspace(text[i]))

i++;

// Find word end

int start = i;

while ((i < n) && !isspace(text[i]))

i++;

if (start < i)

Emit(text.substr(start, i - start), "1");

}

}

};

REGISTER_MAPPER(WordCounter);

// User’s reduce function

class Adder : public Reducer

{

virtual void Reduce(ReduceInput *input)

{

// Iterate over all entries with the

// same key and add the values

int64 value = 0;

while (!input->done())

{

value += StringToInt(input->value());

input->NextValue();

}

// Emit sum for input->key()

Emit(IntToString(value));

}

};

REGISTER_REDUCER(Adder);

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

ParseCommandLineFlags(argc, argv);

MapReduceSpecification spec;

// Store list of input files into "spec"

for (int i = 1; i < argc; i++)

{

MapReduceInput *input = spec.add_input();

input->set_format("text");

input->set_filepattern(argv[i]);

input->set_mapper_class("WordCounter");

}

MapReduceOutput *out = spec.output();

out->set_filebase("/gfs/test/freq");

out->set_num_tasks(100);

out->set_format("text");

out->set_reducer_class("Adder");

// Tuning parameters: use at most 2000

// machines and 100 MB of memory per task

spec.set_machines(2000);

spec.set_map_megabytes(100);

spec.set_reduce_megabytes(100);

// Now run it

MapReduceResult result;

if (!MapReduce(spec, &result))

abort();

// Done: ’result’ structure contains info

// about counters, time taken, number of

// machines used, etc.

return 0;

}The user program has 3 parts: map function, reduce function, and configuration. Most of the heavy lifting is handled by the imported mapreduce library.

The map function splits the input text into words and emits key-value pairs. For instance, “the quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog” is mapped to these key-value pairs: [“the”:1, “quick”:1, “brown”:1, “fox”:1, “jumps”: 1, “over”:1, “the”:1, “lazy”:1, “dog”:1]. Notice that the pair (“the”: 1) is emitted twice.

The reduce function operates per key. For instance, given the input [“the”:1, “the”:1”, “the”:1] it would emit (“the”:3).

The config handles input-output, formats, and the number of resources available for the MapReduce job.

In less than 100 lines of code, we can solve the word counting problem by utilizing 1000s of machines! That’s pretty neat and shows how powerful of an abstraction MapReduce is.

Gathering requirements

With the paper as our inspiration, let’s start outlining the requirements for our implementation:

The user imports our MapReduce library, implements Map and Reduce functions, and provides configuration.

When a user executes the binary, it is copied to multiple machines where it executes in either Mapper or Reducer mode.

Those machines must have access to input data.

Outputs of mappers must be available to reducers.

The user can access the final results.

Infrastructure

When I started working on this, these requirements presented two main unknowns: how to distribute the binary to other machines and how to make input data available to them.

After some research, I settled on hosting my input data on a networked storage server - I chose NFS. We can mount the networked directory on every machine and allow the machines to read and write to it. It won’t be as performant or scalable as Google File System or HDFS, but it will do for our purposes.

To distribute the binary to multiple machines, execute it, and monitor its status, we could probably get quite far by copying the binary via SCP, SSHing into machines, executing the binary, and then waiting for it to finish. We could even implement health-pinging and progress-reporting.

However, after twiddling my thumbs for a while, I realized that this sounds awfully like cluster orchestration and decided to leverage Kubernetes to make my life easier. We can build the binary as a docker image and execute it as Kubernetes Jobs. Integrating NFS with Kubernetes is easy enough via Persistent Volumes and Persistent Volume Claims. Don’t worry, you don’t need to understand these concepts, but I mention them for completeness.

Since I’m developing this for educational purposes, I use minikube to spin up a local virtual cluster on my laptop. I run my NFS server as a docker container outside the cluster and connect it to the cluster via docker networking. The advantage of this setup is that it can be easily migrated to several physical or virtual machines.

With infrastructure sorted out, let’s start writing our MapReduce framework!

Using my MapReduce

First, we’ll explore how to solve the word-counting problem using my MapReduce implementation. Then, we’ll deep dive into the implementation to understand how individual components function.

As promised, I tried to keep the usage semantics similar to the original paper. Compare this MapReduce program using my Go implementation against the C++ example we saw before!

// main.go

import (

…

"github.com/MichalPitr/map_reduce/pkg/config"

"github.com/MichalPitr/map_reduce/pkg/interfaces"

"github.com/MichalPitr/map_reduce/pkg/mapreduce"

)

type WordCounter struct {

wordRegex *regexp.Regexp

}

func (wc *WordCounter) Map(input interfaces.MapInput, emit func(key, value string)) {

text := input.Value()

text = strings.ToLower(text)

words := wc.wordRegex.FindAllString(text, -1)

for _, word := range words {

emit(word, "1")

}

}

type Adder struct{}

func (a *Adder) Reduce(input interfaces.ReducerInput, emit func(value string)) {

val := 0

for !input.Done() {

num, err := strconv.Atoi(input.Value())

if err != nil {

log.Printf("Failed converting input to integer, skipping: %q", input.Value())

input.NextValue()

continue

}

val += num

input.NextValue()

}

emit(strconv.Itoa(val))

}

func main() {

cfg := config.SetupJobConfig()

log.Printf("cfg: %+v", cfg)

cfg.NumReducers = 2

cfg.NumMappers = 4

cfg.Mapper = &WordCounter{wordRegex: regexp.MustCompile(`\b\w+\b`)}

cfg.Reducer = &Adder{}

mapreduce.Execute(cfg)

}Let’s spend some time understanding how my solution works behind the scenes. We can reference a handy diagram from the paper illustrating this.

The user’s program is executed in three modes, Master, Mapper, and Reducer, on different machines. At a high level, the master handles the entire job orchestration, mappers do the expensive map operation over input files, and reducers combine intermediate results from mappers. In my solution, the mode is determined by a CLI flag, e.g. --mode=master for master mode.

Master

Master mode splits input files into subsets, prepares NFS directories, launches mapper jobs with assigned files, and waits for them to finish. Then it repeats the process for reducers. The main master function is simple enough that I can list it here:

// /pkg/master/master.go

func Run(cfg *config.Config) {

clientset := createKubernetesClient()

numNodes := getNumberOfNodes(clientset)

mustValidateConfig(cfg, numNodes)

jobId := fmt.Sprintf("job-%s", time.Now().Format("2006-01-02-15-04-05"))

log.Printf("Running master: %s", jobId)

mustCreateJobDir(cfg.NfsPath, jobId)

fileRanges := partitionInputFiles(cfg.InputDir, cfg.NumMappers)

t0 := time.Now()

launchMappers(cfg, clientset, jobId, fileRanges)

waitForJobsToComplete(clientset, jobId, "mapper")

log.Printf("Mappers took %v to finish", time.Since(t0))

t1 := time.Now()

launchReducers(cfg, clientset, jobId)

waitForJobsToComplete(clientset, jobId, "reducer")

log.Printf("Reducers took %v to finish", time.Since(t1))

log.Printf("Total runtime: %v", time.Since(t0))

}Let’s understand the launchMappers function. It creates a Kubernetes job for each mapper. The job spec specifies:

Docker image containing our binary.

CLI arguments necessary for the mapper: mapper mode, input/output dirs, and files to process.

How to mount the NFS storage.

Wait…Docker image? We never created one! I’ll show this in more detail when we finally run our solution, but Kubernetes revolves around containers so we dockerize our binary so that Kubernetes pods can download the binary.

After launchMappers creates a mapper job, Kubernetes assigns jobs to nodes within the cluster, starts the containers, and monitors their status.

Now that we can run mappers, it’s time to learn how they work!

Mappers

In mapper mode, the binary scans input files line-by-line and passes the line to the user’s map function. Map processes the text and emits key-value pairs using the injected emit function.

In my implementation, the emit function is super simple - it stores the key-value pairs in a map of dynamic lists. A more complete implementation would do some buffering and then flush the buffer to the disk.

When the mapper finishes processing all inputs, it saves sorted key-value pairs to intermediate files in the NFS storage from where reducers will later read them for the final processing. Let’s zoom out here and see how this mapping from intermediate files to reducers works.

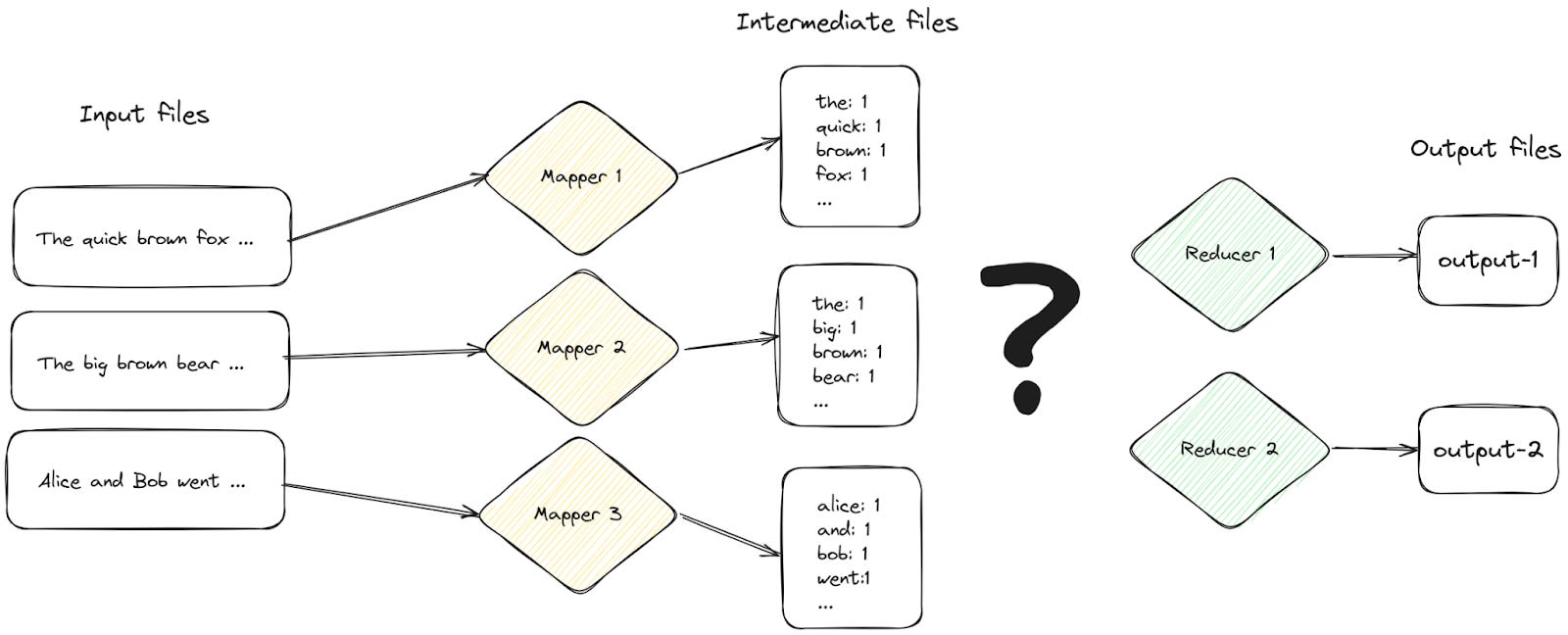

We want to partition the intermediate files by keys such that all the same keys are processed by one reducer. For instance, “brown” and “the” appear in Mapper 1 and Mapper 2 intermediate files. We want to ensure each ends up being processed by the same reducer. Let’s see an example.

To achieve this, when we save intermediate results from mappers, we partition the keys by the number of reducers R using the formula

For instance, using FNV hash and R = 2, we get

(maths note: this reads as “1 is congruent to FNV(brown) mod 2”.)

Based on this, we assign “brown” to the 2nd intermediate file, which is to be processed by reducer 2. Notice how in the example above, all “the”s landed in the blue files, while all the “brown”s landed in the red files!

This concludes the discussion on mappers - next, let’s see how reducers work.

Reducers

As highlighted previously, the reducer’s job is to read key-value pairs from the assigned intermediate files and process them using the user-defined reduce function.

We can be certain of two things: the keys in intermediate files are sorted by key and if a key A is present in one of these intermediate files, we are guaranteed that key A is not present in any file assigned to other reducers.

I tried to be smarter about my reducer implementation and avoid loading all intermediate files into memory. This comes with an interesting algorithmic problem:

Suppose we are trying to process 3 intermediate files, key-value pair at a time without loading everything into memory.

We can merge the key-value pairs on the fly using a min-heap! We load the first key-value pair from each file into the heap. Whenever we pop from the heap, we read the next line from the corresponding file and push it onto the heap. This gives us a memory-efficient way to read a stream of key-value pairs! You can find the implementation here.

After processing all intermediate files, the reducer saves results to the NFS storage.

For instance, the above example would yield: [“abby”: 1, “alice”: 3, “bob”: 2, “car”:2, “dog”:1, …].

The MapReduce paper introduces a couple of additional optimizations that I skipped in my implementation. Astute readers can probably come up with some already - for instance, couldn’t we optionally do some reduction already on the mapper?

Congratulations, you now have a pretty complete understanding of MapReduce! The hard part is over! Let’s put it together and count the word frequencies in the top 100 most popular books on Project Gutenberg using our MapReduce!

MapReduce in action

I downloaded the 100 most popular books on Project Gutenberg to /mnt/nfs/input/ with this script. The book files are labeled book-0 to book-99. I also created a 4-node minikube cluster with access to my NFS storage.

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs$ kubectl get nodes

NAME STATUS ROLES AGE VERSION

multinode Ready control-plane 27d v1.28.3

multinode-m02 Ready <none> 7d2h v1.28.3

multinode-m04 Ready <none> 7d1h v1.28.3

multinode-m05 Ready <none> 7d1h v1.28.3I will be reusing the word-frequencies Go main file I showed earlier. We must prepare the docker image using this Dockerfile and push it to my registry. The mapper and reducer nodes will pull this image to run our workloads.

docker build -t michalpitr/mapreduce:latest .

docker push michalpitr/mapreduce:latestNow all we need to do is run the master locally!

go build .

./map_reduce --mode=master --image=michalpitr/mapreduce:latest --input-dir /mnt/input/ --nfs-path /mnt/nfs/Let’s inspect the execution logs.

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:~/code/map_reduce$ ./map_reduce --mode=ma

ster --image=michalpitr/mapreduce:latest --input-dir /mnt/nfs/input/ -

-nfs-path /mnt/nfs/

2024/04/28 17:13:53 Running master job-2024-04-28-17-13-53

2024/04/28 17:13:53 Creating mapper-0 for book-0-30

2024/04/28 17:13:53 Creating mapper-1 for book-31-53

2024/04/28 17:13:53 Creating mapper-2 for book-54-76

2024/04/28 17:13:53 Creating mapper-3 for book-77-99

2024/04/28 17:13:53 Waiting for jobs to finish.

2024/04/28 17:14:03 Waiting for jobs to finish.

2024/04/28 17:14:13 Waiting for jobs to finish.

2024/04/28 17:14:23 All jobs completed.

2024/04/28 17:14:23 Mappers took 30.1843218s to finish

2024/04/28 17:14:23 Creating reducer-0

2024/04/28 17:14:23 Creating reducer-1

2024/04/28 17:14:23 Waiting for jobs to finish.

2024/04/28 17:14:33 All jobs completed.

2024/04/28 17:14:33 Reducers took 10.106014703s to finish

2024/04/28 17:14:33 Total runtime: 40.290376921sThe whole job took 40s. We aren’t expecting anything crazy here, after all, I’m running this on an underpowered laptop and not a real cluster.

Let’s walk through this a little. The master creates 4 mappers, each with an assigned book range.

Using kubectl, we can see that the cluster is creating 4 containers. This is when the cluster pulls the image we pushed earlier!

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

mapper-0-zgz24 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 11s

mapper-1-m824k 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 11s

mapper-2-ctqqt 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 11s

mapper-3-l2ddh 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 11sThese don’t take very long to start running and to finish.

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

mapper-0-zgz24 1/1 Running 0 18s

mapper-1-m824k 0/1 Completed 0 18s

mapper-2-ctqqt 0/1 Completed 0 18s

mapper-3-l2ddh 0/1 Completed 0 18sThe master periodically polls the Kubernetes API server for the status of these jobs. Once they are all finished, it launches the reducers.

Before we go to reducers, let’s see the intermediate files produced by one of the mappers:

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs/job-2024-04-28-17-13-53/mapper-3$ ls

partition-0 partition-1Inspecting the end of partition-1 shows key-value pairs of a character from Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground. So far so good!

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs/job-2024-04-28-17-13-53/mapper-3$ tail partition-1

zverkov,1

zverkov,1

zverkov,1

zverkov,1

zverkov,1

…Next, the master launches reducers,

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

…

reducer-0-4xt58 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 2s

reducer-1-xvhfk 0/1 ContainerCreating 0 2swhich swiftly finish.

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs$ kubectl get pods

NAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

…

reducer-0-4xt58 0/1 Completed 0 7s

reducer-1-xvhfk 0/1 Completed 0 7sThat’s it - we just computed word frequencies using our very own MapReduce framework! Let’s see what we can learn from the results!

I can see the output files in the root of the job folder:

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs/job-2024-04-28-17-13-53$ ls

… reducer-0 reducer-1Let’s use grep to find the frequencies of some words.

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs/job-2024-04-28-17-13-53$ grep -w zverkov reducer-0 reducer-1

reducer-1:zverkov,112

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs/job-2024-04-28-17-13-53$ grep -w the reducer-0 reducer-1

reducer-1:the,822175

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs/job-2024-04-28-17-13-53$ grep -w mapreduce reducer-0 reducer-1

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs/job-2024-04-28-17-13-53$

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs/job-2024-04-28-17-13-53$ grep -w map reducer-0 reducer-1

reducer-1:map,188

michal@michal-ThinkPad-T490s:/mnt/nfs/job-2024-04-28-17-13-53$ grep -w reduce reducer-0 reducer-1

reducer-0:reduce,123Unfortunately, there are no mentions of MapReduce in the top 100 most popular books on Project Gutenberg… maybe one day?

One final note, notice how these output files partition the result space by key. When we look for a word, it’s only present in one file! It’s almost as if we did something right!

If you made it this far, you might as well check out the GitHub repo. You’ll already be familiar with most ideas!

Congratulations, you made it! If you enjoyed this deep dive, you might enjoy my previous one into SQLite storage format internals. Researching and writing these articles takes a lot of time and effort. To ensure you don’t miss the next one, consider subscribing or following me on LinkedIn.

the repo is not accessable now